Intention and Patience: the Earliest Photographs

Written by Olivia Samse, Collections Intern

Introduced to the public in France in August 1839, the daguerreotype (duh-gair-uh-tahyp) was the very first widely accessible photographic process. Invented by Frenchman Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, daguerreotypes would alter how we see humanity. Before the innovation, the documentation of people was rather limited in its nature. The only way to know someone’s true appearance was to see them in person. Daguerre’s development of accurate documentation would allow for the preservation of people, their families, and would ultimately contribute to the world’s collective memory.

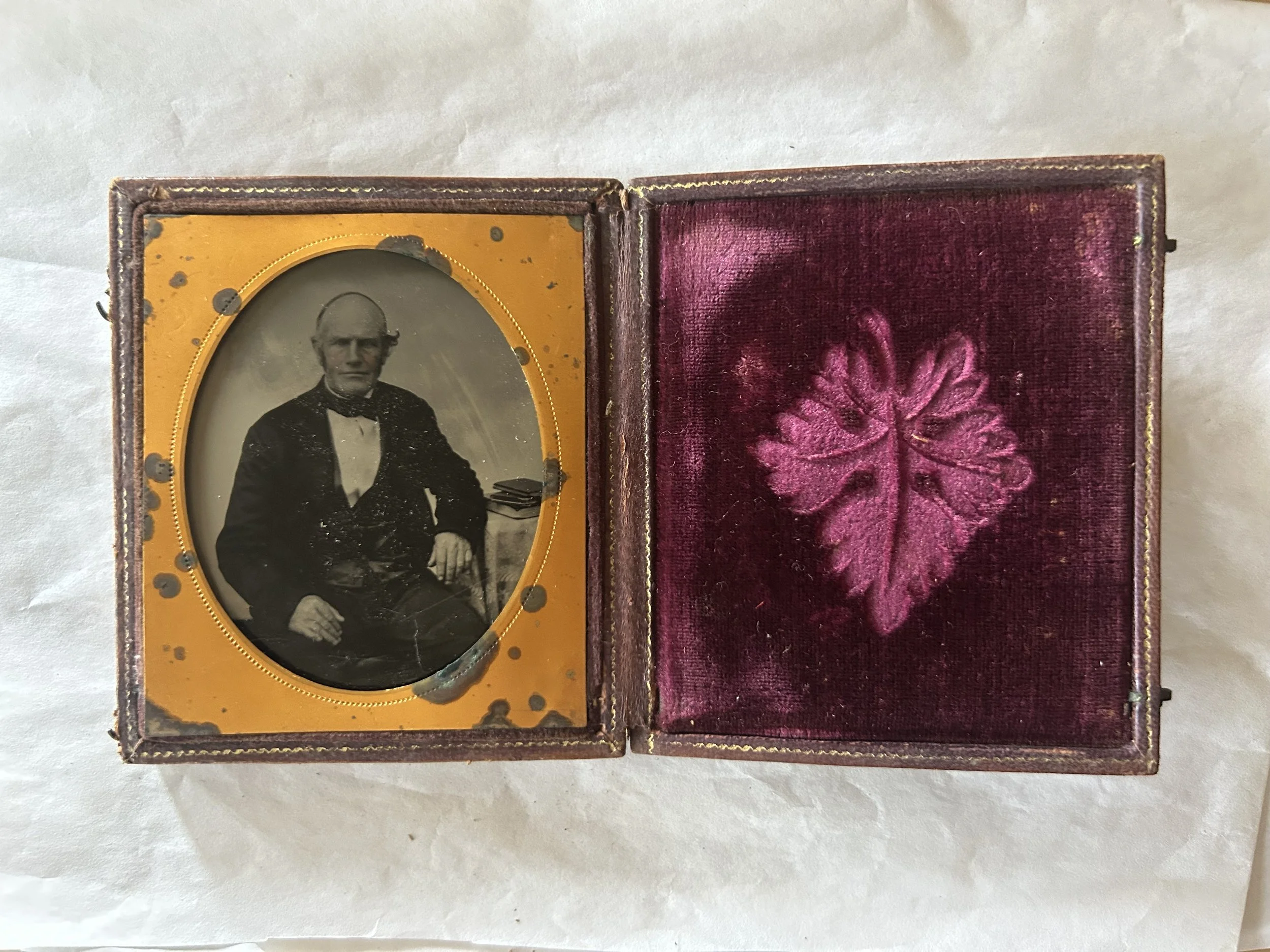

Arriving in America in the mid-19th century, the daguerreotype required great care. Each silver-coated copper plate is a unique photograph.

The plate had to first be cleaned and polished to the pristine clarity equivalent to that of a mirror. Second, the plate had to be ‘sensitized,’ or primed, in a box filled with iodine until reaching a yellow-rose appearance. The plate would now be receptive to light and placed into a camera obscura (Latin for “dark room”), where the only outside illumination allowed in was through a single small pinhole, or aperture, covered by a lens. A lengthy exposure time would range from three to fifteen minutes, making portraiture nearly impractical.

Subsequently, modifications to the sensitization process, along with improvements in photographic lenses, reduced this time to less than a minute. There’s a certain duality present within daguerreotypes. The daguerreotype must be displayed at just the right angle for the image to be visible, otherwise, all disappears and the plate reverts to a mirror. This spectral nature gives in to an eerie or even mystical quality.

Daguerreotypes from the Lott House Collection

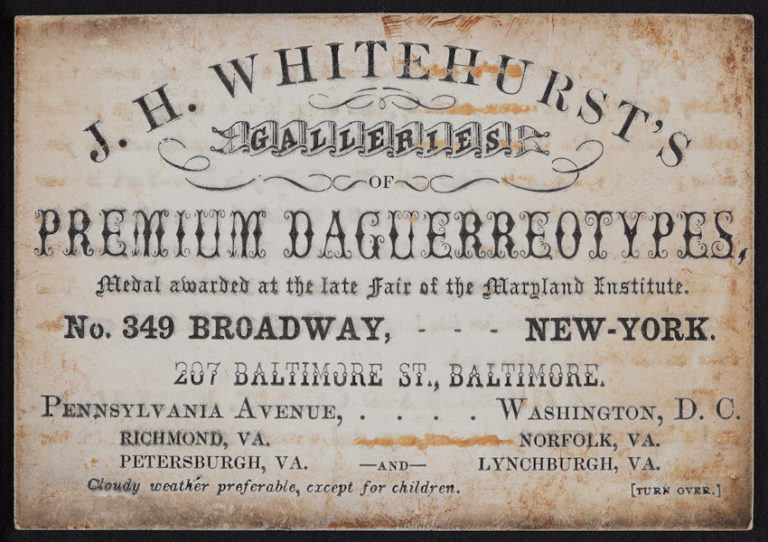

The picture-taking process itself was timely in manner. A single exposure for a portrait could range from just a few minutes to as much as 20-30 minutes. To ensure people would not move during exposures, photographers would place iron stands, arm or head rests behind the sitters for each portrait. Looking closely, one can often find the base of such stands behind the feet of the subject or even a blur on the image from a fidgety kid. Timely in their nature, daguerreotypes were also quite costly: about five dollars at the time (or about a week’s wages), so the majority of people could not afford them.

The Lotts acquired wealth around the mid-1800s through increased farming production. They were fortunate to have the opportunity to enjoy this luxury of having daguerreotypes taken. Within our collection, there are a total of 31 daguerreotypes of men and women. A handful of these photographs are damaged due to improper storage and oxidation over time; however, several remain in great condition.

Daguerreotype case from the Lott House collection

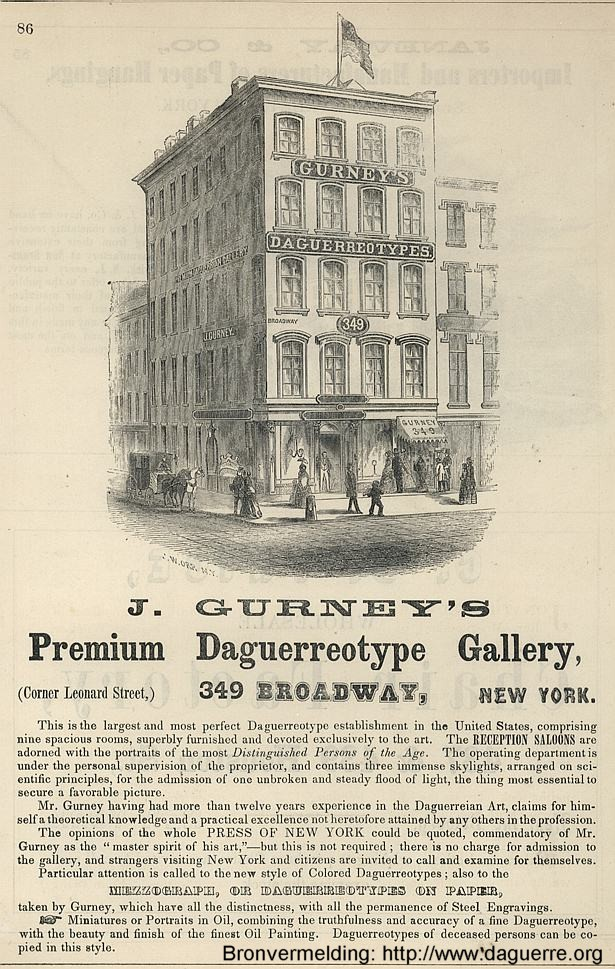

Daguerreotypes reached their popularity as American photographers quickly capitalized on the invention. In 1850, New York City alone had more than 70 daguerreotype studios. Although unique images, daguerreotypes could be copied through a second daguerreotyping process, lithography, or engraving. Portraits based on daguerreotypes often appeared in periodicals and books. They were also preserved in decorative frames or cases, which are just as beautiful as the images themselves.

The limitations of daguerreotypes led to the development of two new types of photographs: ambrotypes, introduced in 1851, and tintypes, introduced in 1853. They were created with a much shorter exposure time, had cheaper production costs, and did not have to be tilted to a certain angle to view the image. Ambrotypes ranged from $0.25 to $2.50 in the United States. They would make photography both more affordable and accessible to middle- and working-class people.

The ambrotype would take over the popularity of the daguerreotype and essentially displace it by 1860. Tintypes were produced from the 1850s to the early 20th century. By the 1940s, a tintype cost about 25 cents, meaning almost anyone could afford a photograph.

The transition of photography from a luxury to a common practice happened rather rapidly. How everyday people see and recall themselves was memorialized and completely modified through innovation.