HOUSE & FARM HISTORY

HOUSE & FARM HISTORY

HOUSE & FARM HISTORY

THE LOTT HOUSE

“…the finest country house in Kings County”

– CHARLES ANDREW DITMAS, 1909

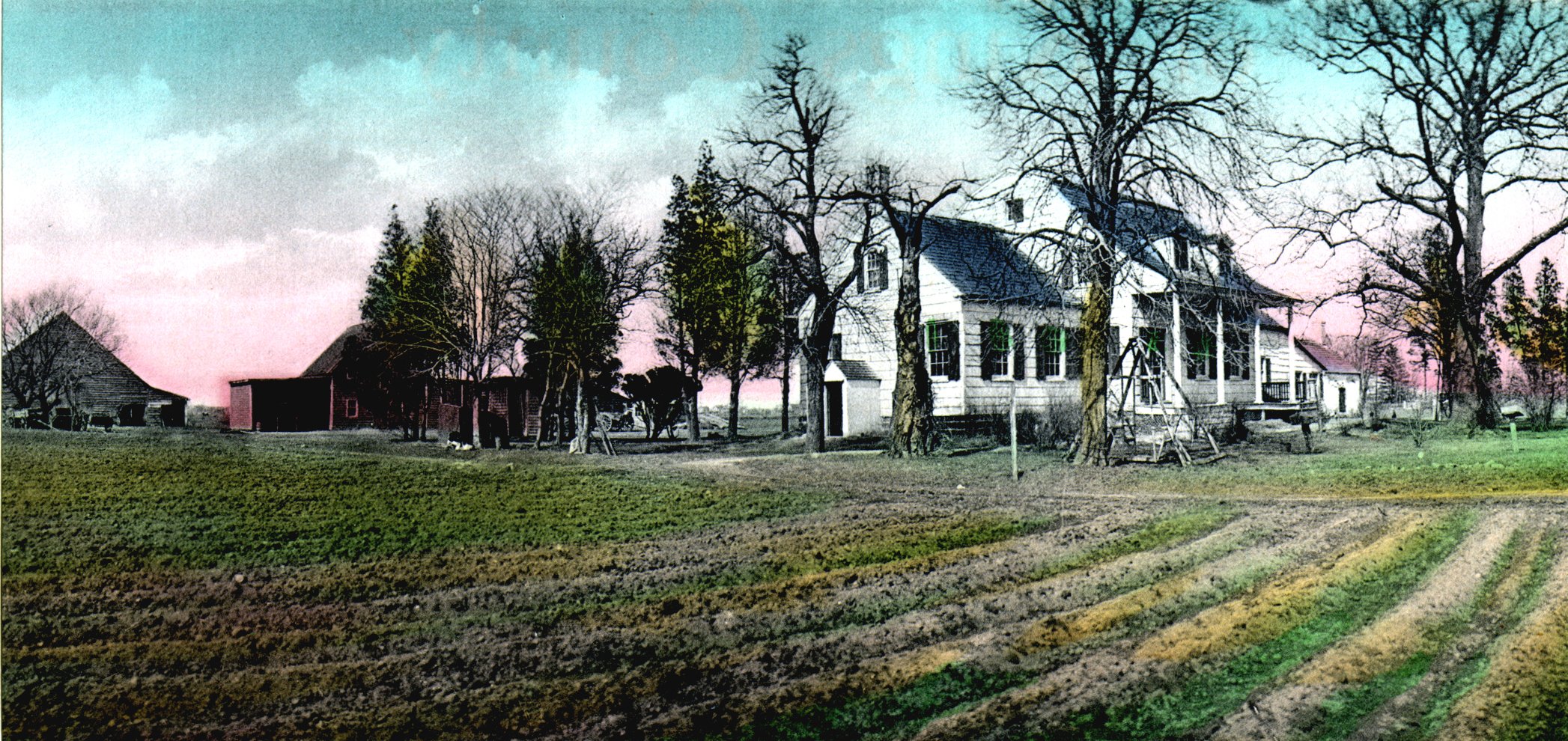

The exterior of the Lott House represents a traditional Dutch-American vernacular farmhouse. Built c. 1800 by Hendrick I. Lott, it incorporates the 1720 house built by Hendrick’s grandfather, Colonel Johannes H. Lott.

The vernacular style of the house is limited to the exterior; the interior exhibits a much grander style. High ceilings and decorative fireplace mantles and moldings highlight Hendrick’s skill as a professional house carpenter in Manhattan during the last decade of the 18th century. Decorative and architectural features in the house date from the 18th through early 20th centuries. At present, the interior of the house remains un-restored.

The eastern wing of the Lott House is the original 1720 house. It has been theorized that this house was along Kimball’s Road (not to be confused with present-day Kimball Street). Kimball’s Road ran approximately along East 38th Street. It was the 19th-century address of the Lott House, and a driveway turned off of East 38th Street onto the Lott property. It is more likely the 1720 house originally stood where East 36th Street is now.

The Lott House is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a New York City landmark. New York City purchased the house in 2002 from the estate of Ella Suydam, a direct descendant of Hendrick I. Lott and his grandfather Colonel Johannes H. Lott.

THE LOTT FARM

Colonel Johannes H. Lott purchased a 220-acre farm property from Coert Voorhies in the town of Flatlands on December 12, 1719. The property was located between (present-day) Kings Highway (to the north), Flatbush Avenue (to the east), Gerritsen’s Creek (to the west), and the Atlantic Ocean (to the south).

The property and house were well-situated, located near a tidal creek, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean. This creek has been known by several names since the 1600s: Strome Kill, Ryder Pond, Gerritsen’s Creek, and presently Marine Park Creek. It was along the western shore of this creek that Wofert Gerritse established a grist mill in the 1600s. The many creeks along the southern shore of western Long Island were dotted with mills to process grains into flour.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1916

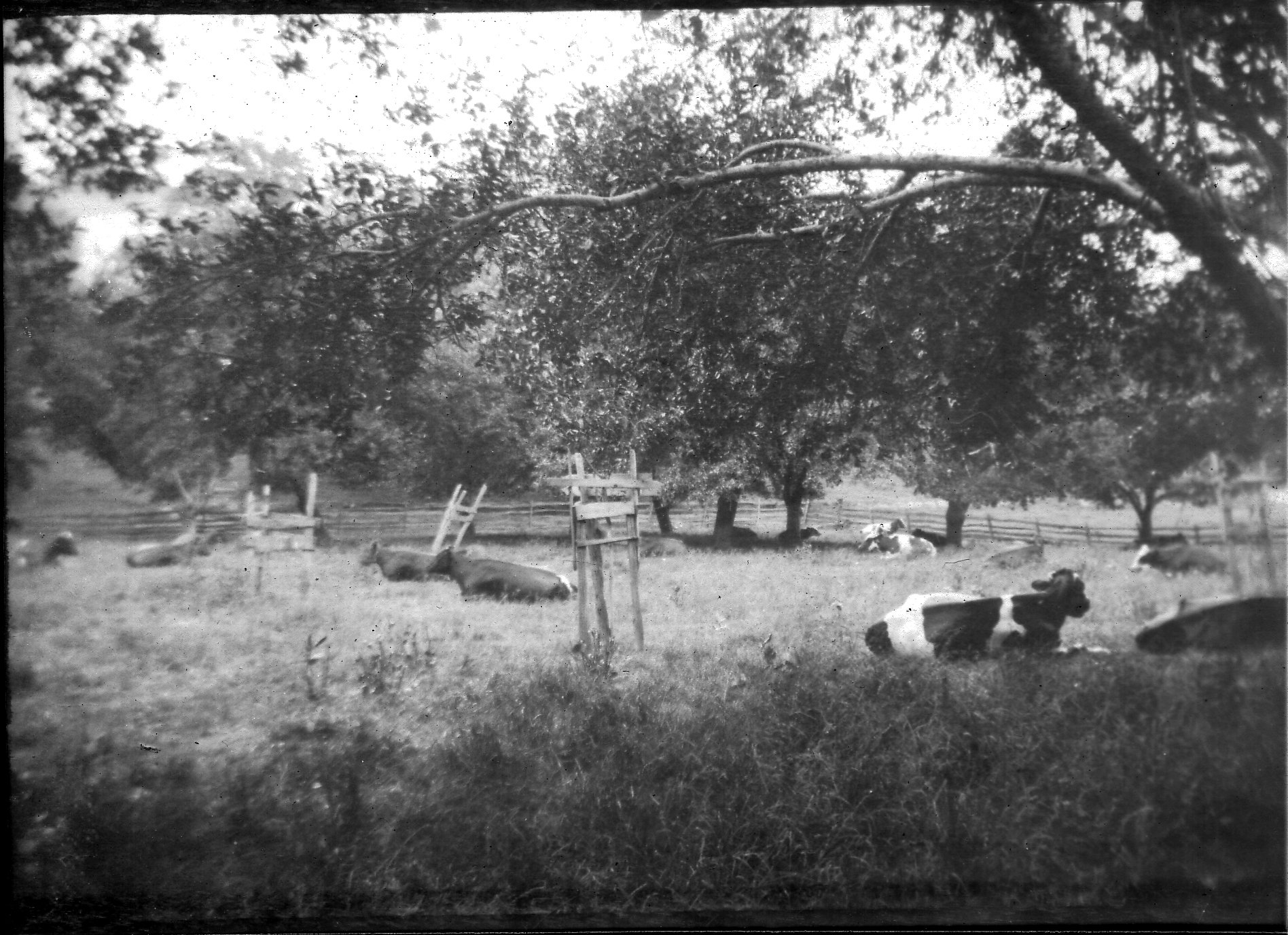

Johannes H. prospered in the area. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the farm grew staple crops of wheat, rye, buckwheat, oats, corn, flax, and barley, while fruits and vegetables were mainly grown for family consumption. The farm’s location near the water, and the salt hay that grew along the marshy banks, were a perfect source of fodder for grazing cows and cattle. In addition, they raised cows, hogs, and chickens.

Kings County was the second largest agricultural producer in the region; Queens County was the largest. The network of large family farms made extensive use of enslaved peoples for house and farm work. The Lott’s large tracts of land were worked by enslaved labor. Johannes E. Lott enslaved twelve people according to his 1803 probate.

The focal point of the Lott farm was the house. The surrounding area contained several barns and other buildings. The diary of Flatlands farmer John Baxter states that he and the town residents helped Hendrick and his family raise ‘several large barns on the Lott’s property’ in the summer of 1796. Much of the farm layout has remained the same into the early 20th century. Fields were located to the east, behind the stone kitchen, and to the west, from the house to the creek. To the north was the barn complex with supporting buildings.

Gertrude Vanderbilt (1824-1902) described the farmlands of her childhood in her 1881 book The Social History of Flatbush:

“The head of every family in Flatbush, with few exceptions, was a farmer … They cultivated their land in the most careful manner, and were among the best farmers in the State.

It was rarely that one saw old and dilapidated outhouses or broken fences… In the southern section of the town stones were scarce, so that the fences were post and rail… There was formerly a stone wall running on the easterly side of the road that led from Bedford southward toward Canarsie...

Little red chipmunks might be seen skipping over and through the interstices of this wall, for it was then a quiet nook, and the cultivated fields, shut in from the cold winds by the woods at the north-east, were always rich with the beauty of waving grain in the various stages of growth as the season advanced.

Here the running blackberry vines twined and interlaced themselves in arabesque figures across the stone wall, their prickly stems and the toppling stones serving to protect the enticing fruit. High stalks of the goldenrod in the autumn, and celandine and wild roses hid their roots in the soil, kept damp by the fallen stones...”

FARM HISTORY (CONTINUED)

The 1865 Agricultural Census valued it at approximately $24,000, the second highest value of the 70 recorded farms in Flatlands. In 1875, the farm totaled 226 acres. That same year it produced 33,000 heads of cabbage.

By the 1880s, the Lotts began to switch their crops from an emphasis on grains to fruit and vegetables as competition from distant markets grew. Another change was the growing reliance on hired labor as the children attended school and university. According to Jeremiah Lott, many farms hired Irish, German, and Italian immigrants. Census records indicate that servants and farmhands continued residing on the property into the 20th century.

Although Federal and State farm records do not exist for the beginning of the twentieth century, we know the Lotts continued to farm vegetables and maintain some dairy production. They also expanded into oyster farming toward the end of the 19th century.

During the first decade of the 20th century, the property shrunk to approximately 30 acres. Even so, the farms still prospered and hired farmhands. Andrew Suydam, interviewed by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in September 1916, discussed the importance of the local farms in feeding the city and noted that it had been one of his best harvests. That year they had a record crop of potatoes, harvesting 16,000 bushels, approximately 880,000 lbs of potatoes.

Having sold much of the farmland at the turn of the century, the area surrounding the house was re-landscaped. This renovation added new bluestone paths and a tennis court to the front yard. Selling the farmland would eventually become more profitable than continuing to farm. Many of Brooklyn’s farms sold off their land and moved elsewhere.

John Bennett Lott, George Lott, and Andrew Suydam were the last of the Lott farmers. John B. Lott died in 1923. The last harvest in 1925 was followed less than a year later by the city laying water lines throughout the former farm fields and the rapid onset of residential development. Instead of moving, Jennie and Andrew kept the family home with ¾ of an acre surrounding it.